In these days of grief and astonishment, we may be tempted to seek refuge. To look the other way, to change the channel, to think that we are far away and, anyway, what could we do? To want to flee from anguish is human; it is more human to choose to harbor it, and to avoid the easy shortcut of cynicism.

It is not easy to live in a world where atrocities like the ones we have witnessed these days can take place. But the risk of giving in to despair or disengagement is too great.

A few years ago I interviewed the pacifist and international mediator Scilla Elworthy, founder of the Oxford Research Group, an NGO she created in 1982 to establish a dialogue between the world’s nuclear weapons policy makers and their critics, for which she received three Nobel Peace Prize nominations.

Our conversation stayed with me. Scilla pointed out in no uncertain terms the importance of the “human factor” in helping to resolve long-standing, seemingly intractable conflicts. Above all, to be able to listen to the emotions and needs behind the other’s positions and claims, and for the other to be able to listen ours. This seemingly simple proposition requires enormous courage, and a determined commitment to our common humanity.

She told me about activists like Pakistan’s Gulalai Ismail, who together with other courageous youths, through the Youth Peace Ambassadors, managed to disarm almost 200 young suicide bombers by seeking them out in their villages and talking to them, with an open and respectful disposition.

Scilla stresses the role of women in peace negotiations: “Women consult with the victims of war – the teenage orphans, the mothers of the disappeared, the starving widows in destroyed homes – to bring their concerns, which would otherwise go unnoticed, to the table”, she says. “They emphasize needs over ‘bottom lines’; e.g. they insist on attention to re-hab of the wounded, PTSD, care of war orphans, burial of the dead. This is why involving women in peace negotiations lowers the likelihood of conflict resurgence, and invites the participation of the population as a whole.”

In fact, she shared, “A statistical analysis of 182 signed peace agreements between 1989 and 2011 revealed that peace agreements where women are involved are 35% more likely to last for fifteen years.”

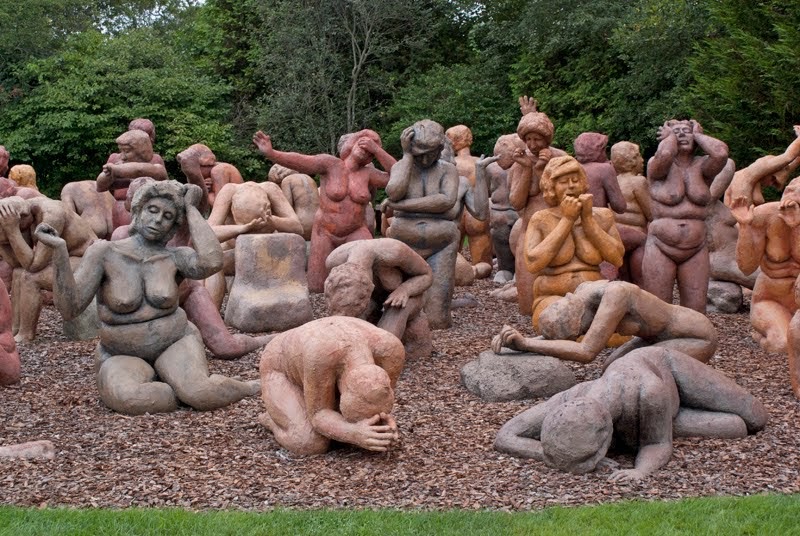

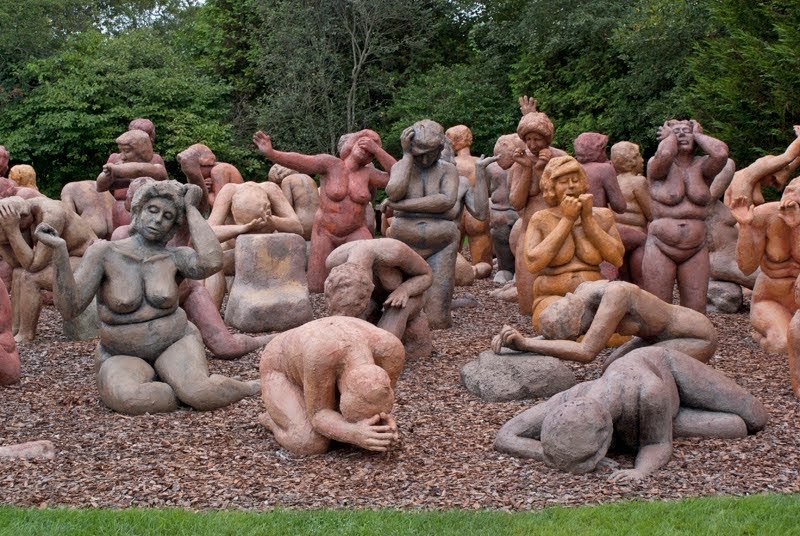

Sadly, peace negotiations or agreements are nowhere in sight? We live in the arms of heartbreak: aching for the lives atrociously cut short; holding our breath for the hostages and what they must be living through; fearing for the suffering of on both sides that will surely grow like a cancer with the escalation to come.

Why, then, talk about women and their protective impulse?

Because the fierce loyalty that was born millenia ago, in the light of the maternal-filial bond, among ancestors so remote that they did not even have a name, remains a beacon for humanity.

The beacon of compassion does not belong to one gender, to one nation, to one class of people. It knows of no causes nor enmities: all children are its children; all elders, its elders; all lives, its lives.

The crimes that have been perpetrated, and those yet to come, violate this foundational principle. But they cannot destroy it; not if enough of us gather around its fire, shield it, defend it.

May that boundless belonging help illumine, protect, and once again enthrone the deep wisdom of the heart.

In these devastated days, may we be able to say, with the poet Adrienne Rich:

“My heart is moved

for all that I cannot save:

So much has been destroyed.

I must cast my lot with those

who, time after time, tenaciously,

without extraordinary power,

reconstitute the world.”